One of the things I like as much as maps and geography is linguistics and anything related to the study of language. When it comes to maps, the naming of places is something I’m particularly fond of. Contrariwise, there’s nothing worse than encountering a map for a book or game adventure littered with the most overblown of PanCeltic place names or where the naming is intended to sound exotic through the addition of apostrophes (or sometimes both!).

I think one of the best ways to learn how to create realistic maps is to study real maps and to study why certain places are named the way they are. Names evolve and change over time as successive peoples enter an area and either use existing names given to places by their predecessors or attempt to translate them in some fashion. In some cases, the two cases (descriptive versus folk etymology) can be very hard to differentiate.

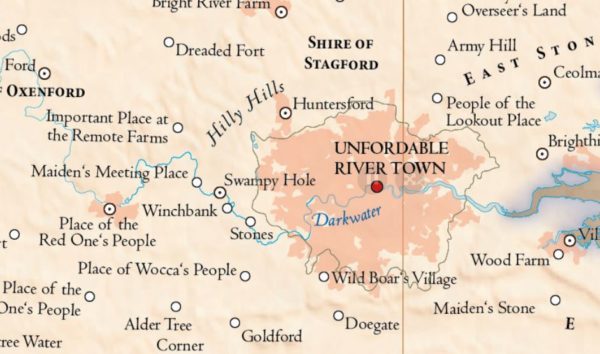

For those creating their own maps, there’s much more flexibility in the etymology of place names and the opportunity to play with the names while simultaneously developing the place names, cultures, history, and language of the area. Descriptive names are easy and incredibly common. Rivers are often named simply “River” such as England’s Thames, Tame, and Teme, and also Avon from a different root. The Atlas of True Names translates the Thames as Darkwater, but that seems more like over-etymologizing since the original root can be used to mean “dark” or “river”, implying that it would be more like a river in the sense of a dark and deep-flowing body of water, much like brook and torrent describe two very different types of streams. Other rivers are simply “river” with the addition of an adjective, such as Mississippi derived from the Ojibwe misi-ziibi (“great riverâ€) or Tolkien’s Anduin and Brandywine (Baranduin).

So whether your fictional kingdom’s river is called The Long River or Darkwater or, simply, The River, there’s no wrong way to do it. Though I beg aspiring fantasy cartographers to not be too liberal with place names like Skull Mountain or Ul’za’kamm’dng. Simple and consistent is always better and you can get a lot of mileage out of simple fantasy base roots for river and mountain. For myself, I prefer Ered Luin to the Blue Mountains, but that might just be because I’m a fan of Elvish etymology, even if it is pretend.