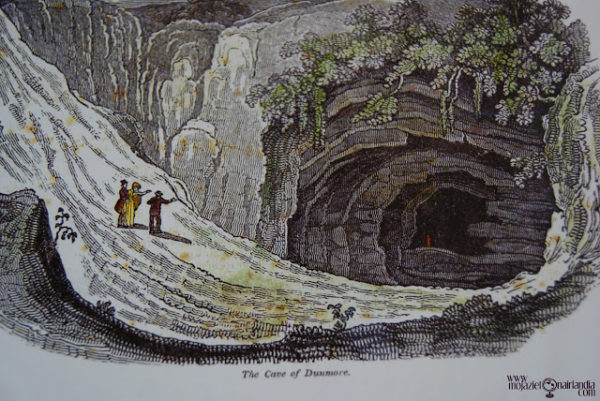

As caves go, the Cave of Dunmore in County Kilkenny, Ireland, is a bit on the small side and not too terribly exceptional. As real-world locations go for the basis of game settings, there’s almost more going on in the visitor center than there is in the actual cave, apart from the somewhat dramatic sweep of the entrance that drops down steeply to the subterranean opening.

The story behind the cave and its history as the site of a Viking massacre is far more interesting and provides plenty of fodder for adventure, particularly if the dark atmosphere and reputation among the inhabitants is played up. For the gamemaster in a hurry, it’s relatively easy to make or find maps of limestone caves that are much more extensive and adapt them for adventure and to borrow all the description needed.

“we having, when led to the cavern for scenic illustration of the facts of this history, adventurously plunged our hand into the clear water, and taken therefrom a tibia of unusual length; and, indeed, the fact that such human relics are there to be seen, almost a quarter of a mile from the light of the earth, must, if we reject the peasant’s fine superstition, show us the misery of some former time of civil conflict, that could compel any wretched fugitive to seek, in the recesses and horrors of such a place, just as much pause as might serve him to starve, die, and rot.”

– from the Dublin Penny Journal, 1832.

Colorized image of Cave of Dunmore via Moja Zielona Irlandia from the original in the Dublin Penny Journal